Evidence

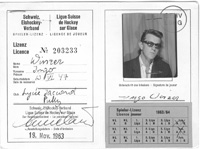

Ingo Winzer

2017

Flashback

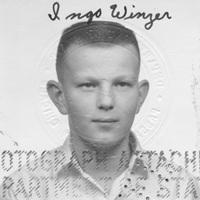

I’m fifteen years old, lying on my stomach at the municipal pool. It’s 1962 in Switzerland. From my family’s house high above Lake Geneva you can see the big blue circle of water fading away down towards the right, and the Alps rising in layers on the left.

I’m at the pool with friends from the Lycee Jaccard, a private boarding school. Their parents have parked them here for various reasons that have nothing to do with academics. Most of the famous Swiss schools will be bust by the end of the decade. I’m a day student. My friends, Augusto Dominguez and Peter Goldmark from Venezuela, Jim Roberts from South Carolina, Billy Stuart from California, Kevin Snow and Erik Martin also from the US, Hans Jorgensen (Jorgy) from Denmark, and Michael Gregory (Peck) from France, are all older than me, as are most of the girls we know.

We never talk about personal things. Four years of being best friends and I never know anything about their families. Do they have brothers, sisters, what work do their fathers do? And once we leave the Lycee, we never hear from each other again. Billy Stuart looked me up a few years later in Boston, but that was it. And I reconnect by chance with Jim Roberts 50 years later.

Another of our friends is Salem Sabah and we know all about his family because they run Kuwait and own most of it. But he’s forbidden to see girls, so he never goes to the pool with us, or to a pizza joint (le Pizza) on a back street in downtown Lausanne where we meet girls from Le Manoir, another boarding school. Beatriz Pike from Palo Alto, Toni Foster from Berkeley, Miriam Coleman and Barbara Dunn from England, Kathy Halle from Cleveland, Suzie Skinner, a Eurasian from Seattle, M’Lisa Young from Utah, Sally Miller from Wisconsin, Leslie McMillen whose father works for Aramco in Saudi Arabia, and my sister Birgit, a year older than me and our connection.

We hang out as a gang on Saturdays and there is distant flirting, but this being the early 1960s I don’t think anybody even gets kissed. I sure don’t, although I brush Miriam Coleman on the cheek when she's boarding a train home one summer. I hope to hold her hand when a group of us go exploring through the large fields above my house, but it doesn’t work out well and depresses me for months afterwards. I always think of Miriam as my girl although I’m aware that we have only a vague knowledge of each other and almost no interaction. In the summers I write her letters that begin “My Dearest Miriam” and end with agonizingly-composed phrases that hint at love without actually saying so.

Several years later when I’m at school in England, I hear she has given her virginity to a Turkish boyfriend. The girls keep in touch. This brutal reminder of the ineffectiveness of my own romantic maneuvers, and the childishness of my ambitions on the scale of relations between men and women haunts me even through the first years of college. I don’t imagine the Turk spent much time holding her hand, and I suspect she was the more willing, the more direct his approach.

I open my eyes to see brown ankles and feet with painted nails, but I’m not sure that I want to wake up. Goldmark and Roberts are propped on their elbows and the girls have just arrived and are standing around in that way that girls can move and still be in the same spot. I think I’m happier being asleep, not having to think what to say and the right time to say it, or what it will mean or what anybody else will think about me.

I finally follow the ankles up to the rest of Beatriz Elena Pike Mendoza, in a yellow bikini she doesn’t quite fill out, especially on top. Her legs are thin and smooth, but with tiny bumps around the knees. She's very pretty despite a poor complexion, with a full sweet smile, brown skin and very thick black hair that often hangs in her eyes. She’s half Salvadoran, the most popular girl in her group and I’m always nervous around her. But she’s not looking at me, never looks at me or anyone very much - not because she’s unkind, just because she’s always busy. Next year she will date an older guy from my school, Pierluigi Locatelli. Later this year I invent a joke about us being married and having children. In reality the idea that I could be her boyfriend would never occur to me, and would be terrifying because she’s too popular. I wouldn’t measure up. Forty years later, when I have a teenage daughter of my own, I realize Beatriz knows as little about boys as I know about girls, and is as anxious as I am to find understanding and recognition.

Beatriz has arrived at the pool with Barbara Dunn and Kathy Halle. I’ll tell you more about Barbara later, but Kathy remains unknown to me throughout the two years she spends at the Manoir. She's a soft Jewish girl from Cleveland, who won’t wear a bikini because she’s a bit heavy and she's mostly silent. She has already grown breasts, though, and I draw her nude in pencil, using tracings from the lingerie pages of the Sears catalog. I trace the outlines, add her face in the rudimentary form of eyes and wavy hair, then incorrectly position nipples and pubic hair where I imagine they might be found. Driving me home from school one night, my father silently hands me several pages of my work. I flush and deny ownership. It’s as close as we ever come to talking about sex.

Throughout much of my life I don’t know what I’m looking for, but it's got a lot to do with girls. Maybe I find it years later when I kiss Sarah Zilske, beautiful but married, and she closes her eyes and runs her tongue over her lips and says, “Oooooooo, that was just as good as I thought it would be.” Or when I kiss Jean Thomas, who tastes of milk, after a wedding in New Jersey, or maybe when Hildy Green kneels on the bed in my small room on Magazine Street in Cambridge and pulls off her T-shirt. But I never know exactly what it is.

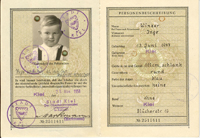

Chapter 1.

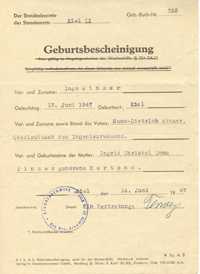

I’m born in Kiel, Germany, in the North - flat country with low villages and sharp steeples and fast-moving clouds, a land of Lutherans. My mother’s family came from here, Schleswig-Holstein. My father’s family originally came from Holland, moved to East Prussia in the 1800s, then finally to Berlin, where he was born. Both my parents were 10 years old when Hitler came to power, 16 when the war started, and just 22 by the time the whole thing was over and most of their friends had been killed. It explains a lot about their later life. My grandfather, Ludwig Martens, who rose from village life to be an official with the Post, had a large fund of stories, making fun of the Nazis and “Adolph”, but my father never said a single word to me about the war. I have a photo of him wearing his uniform and officer’s sword after graduation from the German Naval Academy in 1942 when he was nineteen, ready for U-boot duty. The sword and epaulettes now hang on my wall. Had he stayed in Germany, had I been raised there, my father might have told me about the U-boots, the war, the bombings, the Nazis, what he thought about it all, what the war meant to him and to me, a German kid. But he left Germany behind as soon as possible and probably hoped he was leaving the memories behind, too. So I grow up an American kid who knows nothing about his father.

Many years later, our family visits the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, where one of the exhibits is a German U-boot, sliced down the middle so you can see the inside. It’s tiny. My father says nothing, doesn’t tell me how it works, just stands there a very long time.

Seeing old photos, it’s a shock to find that my mother was pretty, even beautiful. She met my father in Danzig, a port on the Baltic in what was then East Prussia, where he was waiting for his U-boot (U-1164) to be completed at the shipyards and she was studying to be a physical therapist. My father was a lieutenant on U-14 (a training ship), U-1164 (eventually sunk in Kiel harbor) and finally U-3008, a late-model boat taken over by the US and operated until 1952. Towards the end of the war the death rate for U-boot crews going out on patrol was close to 100 percent.

There must have been a lot of hanky-panky going on during the war, because my older sister, Birgit, is born just a few months after my parents marry in 1945.

I’m born a year and a half later, in a restaurant converted to a clinic, where most of the staff are celebrating their new political rights by staying home on strike. A hard-bitten midwife tells my mother during the delivery, “Well, Mrs. Winzer, there’s good news and bad news. The good news is, it’s a boy. The bad news is, that’s the only part of him we can see so far.” A few days later, I’ve developed jaundice and when I’m brought to my mother she says, “That’s the wrong one.”

When I’m older, my mother tells me a few stories about the war. As Kiel is bombed by the British during the day and the Americans at night, she and her parents move from one entrance of the local bomb shelter to another; the first entrance is hit by a bomb and everyone there killed. She points at young men in uniform in old photos and says things like, “He was killed the next month,” or “They were lost on the Russian front.”

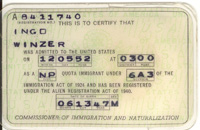

My father is demobilized at the end of the war and drives a truck for the British army, who occupy our sector of the Vaterland. In 1951, now working at Philips, he manages to leave for the United States, sponsored by an uncle in Chicago who dies before my father gets there. Technically, we’re illegal immigrants. My mother joins him later, then returns after six months for my sister and me. During this time Birgit and I live with my grandmother, who seems old to me her entire life, probably because she has a large wart on her nose and false teeth. We sail from Copenhagen to New York on a Norwegian ship, the Stavanger Fjord, then fly to Chicago on a DC-6, a bronco-bucking ride at night. I suffer from motion sickness and vomit on both the ship and the plane.

America is a remarkably generous country. They're in a death struggle with Germany, but as soon as the war ends they welcome us like nothing happened.

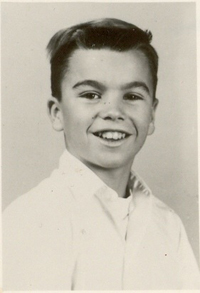

My father was trained as a mechanical engineer at the German Naval Academy and now winds copper wire for electric motors in a Chicago factory. So does my mother, on opposite shifts. I’m enrolled in kindergarten at the Pilgrim Lutheran Day School, where the other kids get excited every time I learn a new English word. After six months, I’m fluent. Later, I’m always the best speller, reader and writer in every school I attend. Now my father gets a new job, selling sawmill equipment, and we move to cold northern Wisconsin, to a place called Marinette. It’s the first of many moves that put me in a new school every year until I’m 13. Always leaving my friends behind, always the new kid.

In first grade, during recess, we do jumping competitions. You stand on a baseline and there are lines painted on the asphalt to measure how far you jump. I’m very good at it, but one day the janitor has put fresh white paint on the lines and as I stand on the baseline, the paint gets on my shoes. I run away with white marks pursuing me, and my footprints remain on the baseline for weeks.

My parents speak English with an accent and I have a funny name that is turned into Igloo, Inkwell and Bingo by my friends. Otherwise everything is pretty normal. We live in a purple-colored house on a street corner. The cellar has walls of stone and dirt and is filled with fat black spiders that I fear. I’m a cub scout. I study my scout manual and ache to earn the achievement medals. I’ve got some good friends, Darryl Evans at first and, after another move, Mike Cavil. Darryl is a tall guy who helps me learn to ride a bike by running alongside, holding the seat. His bike is so big I can only stand on the peddles. At Christmas I get a bike all in pieces that my father has to put together. I play baseball for a team sponsored by the Ansul Chemical Company. I’m the best player on the team, the pitcher, but we’re lousy and never win. Next year I try out for Little League but I don’t really know how to play and I’m cut, my baseball career over until I’m a coach, forty years later. My father takes me to a real baseball game in Milwaukee and comes up with a foul ball. We write the date and other important information on it and it’s placed on my dresser. Immediately I take the ball out to show my friends, we start playing with it and the ball is ruined. Afraid to bring it home, I give it to some kid, then lie to my father that somebody took it. He’s angry and tells me to get on my bike and get that ball back. I cruise for hours with tears in my eyes.

When I'm in fourth grade my sister Birgit has a boyfriend named Dale with a reputation as a hoodlum. I never think much about my sister even though she's my closest friend. I really only notice her years later, once she’s a teenager and has grown breasts. Then I’m always hoping to see her naked. Well, that's what teenage boys think about most of the time - you can't write a kid's story and not mention sex.

My younger sister, Kirsten, is born in 1955 across the river in Menominee, Michigan. I’m eight years old now, so I sometimes have to baby-sit at night, but I’m terrified that she'll cry because I don’t know what to do. Even when she sleeps straight through, my guts are tight as glass. On Saturday mornings there’s a show on TV where you can draw stuff on a plastic sheet that sticks to the screen. You can draw a bridge for the cartoon characters to cross or a tent they can sleep in. We watch the Pinkie Lee show and sixty years later I can still sing the damn jingle.

We go to church and my sister and I go to Sunday school. I learn a lot of bible stories (New Testament) and love the pictures, red, blue and gold. We sing hymns at church and in school and I have a nice high voice. But the whole thing gets tedious for my parents, I guess, because eventually we stop. The war killed whatever faith they might have had - there's never a word about God or religion at home.

In Marinette my sister and I are the smartest kids in school and are sent downtown for day-long testing, answering questions about things we read, and pointing out what’s wrong with pictures we're shown. It seems childish. When I’m older, in the fifth grade, I’m tested again and the teacher calls me up after school and tells me I have special responsibilities because I have a high IQ. I never know exactly how high it is or what those responsibilities are. There are lots of tests given in school at this time. I always score five or six grades above my level and look forward to the tests so I can shine in everyone’s eyes. It never occurs to me that the school is looking for the stupid kids, not the smart ones. I read a sci-fi story about a world where your status is determined by how well you do on tests. You don’t have to take them, but you can’t rise in society without them. The tests are quite complicated, including social skills, but I’m sure that I would become a White Star, the highest rank.

Much later, in high school at the Lycee Jaccard, I make up tests for my friends. Since I design the tests, of course I always score 100 percent. But my friends don’t care, they like to be tested. Through tests I get good grades. Through tests I eventually get into college. I like the idea that someone is watching me, measuring me, that someone is running things. I get the first hint that the real world is different in sixth grade, when we finally get to compete in the state spelling bee. I’m the best speller in the school and should easily make it to the city-wide competition, but right away I trip up on the word ‘soldier’ and am out. Just one mistake and I’m out, without forty-nine other questions to redeem myself. Tracy Katz is sent instead. Later in life, when things don’t work out - with school, with women, when I get kicked out of college, when I’m on my own - I long for the world of tests where I always do well.

When I’m nine my father gets a job with the Warner Electric Brake and Clutch company and we move to Beloit, Wisconsin. First we live in a crummy part of town just a couple of blocks from the black section. The blacks have dirt roads and my friends and I never dare to ride our bikes in there. At school I’m accepted right away because I wear a leather jacket and am good at playground soccer. We play a stupid game that makes you pass out. You hyperventilate, then stick your thumb in your mouth and try to blow hard, while someone wraps his arms around you and squeezes your chest. You pass out immediately, usually for 10 seconds or so. One time the kid who is squeezing me forgets to hold on and drops me right on my face in the gravel. I’m a crossing guard with a white belt across my chest and can arrive late for classes. I’m made a lieutenant and get a badge with blue enamel in the shiny silver. Next year I would be captain, with the red badge, but we move again.

My friend Benny Lathrup lives a block away and we ride our bikes everywhere in the summer, gone for hours, our parents never know where we are. We mainly ride out to the country, to some creeks where we find frogs and lizards and strange shellfish. Once a big kid rides us off the road and demands our money. I give him a dime but it’s a triumph because I secretly have a quarter in my pocket. At a corner shop at the edge of the black section we buy sweet syrups in little wax bottles and licorice rolls, or tasty black wax mustaches and red wax lips that you can chew after you've finished playing with them. At night in our back yard there are masses of fire-flies that we catch and put in bottles. I frequently steal money from my mother, usually just a dime or a nickel, but once I steal two dollars to buy a bamboo fishing pole, not thinking until later that I can’t bring it home and I have to ask Benny to keep it at his house. I always consider him the tough one, but he’s shocked that I would dare to steal from my parents. He’s much too afraid of his father, who sometimes whales the hell out of him for nothing. My mother knows I’ve wanted the fishing pole and a few days later she gives me two dollars to buy it. Now I feel ashamed and guilty but I keep the money.

My father is promoted and we move to a fancy section of Beloit called Turtle Ridge. It’s too far away for my old friends, even by bike, so I have to make new ones again. I start the fifth grade at Morgan Elementary School. My new best friend is Mike Telfer, the leader of our pack, whose parents are interesting because his father has a line of bullet wounds across his back where he was machine-gunned in the Pacific, and his mother often walks her pretty, freckled body around the house in just a bra and panties. We’re only ten or eleven years old but we notice this. She has an interior decorating business, with an office in her house. One day I’m at the house when my sister phones for me. Mike’s mom puts me in her office to take the call and I desperately need my sister to get to the point and get off because I badly have to go to the bathroom. It takes too long, though, because suddenly I feel warm pee down my pant leg and there’s a small puddle building on the floor. Mike’s mom is unfazed, very business-like, moving samples out of the way, and drives me home standing up in the station wagon, but I know that now she’ll always think of me as a little kid. I hate phones for the rest of my life.

Next year, in sixth grade, a group of us go bad. We start smoking and shoplifting, mainly school supplies, cigarettes and lighters. We get good at it, too, one kid distracting the shop owner, others forming a shield, while a couple of kids do the actual stealing. The stealing goes on for six months or so until one by one all the kids get caught, except me, so I decide it’s time to stop. My last stolen item is a blue stapler in a red plastic case, with a white box of staples. It’s small enough to fit in my pocket, but it’s on a big display in the middle of a table so I have to reach far out to get it, waiting for someone to yell, “Hey, kid!” Sixty years later I still feel the sweat.

One of our friends has a shack in his back yard where we smoke and where we keep the cigarettes and lighters we’ve stolen. His parents must know what’s going on, but I guess they don’t care. When we go home we’re reeking but our parents never seem to notice, they all smoke. One time my father smells the fur collar on my leather jacket, asks where I’ve been. I say we lit a fire in a field. I never really learn to smoke properly because I can’t get the stuff into my lungs but I do a good job of faking it, sucking it into my mouth, then holding it for a while before breathing out.

We have BB-gun fights, stalking each other in the woods. The rule is you can only shoot someone below the waist. We wear thick, lined blue jeans but it hurts like hell if you're hit. We used to play with cap guns and could claim the other guy didn't get you; not with BBs. I get a scope for my gun but don't know how to adjust it properly, and when I kill a bird by hitting him in the head, exactly where I aimed with my scope, I'm shocked. I always imagine I'll kill something with my gun, but when it actually happens it's pretty horrible.

Turtle Ridge is separated from the rest of Beloit by half a mile or so of low scrub country, split by a small stream with high banks. I’m riding my bike back late one afternoon and see a load of people a hundred yards up the stream, which is rushing hard after several days of rain. They’re looking for a kid who was playing with a buddy and went under, even though the water is only up to your waist. Finally some men form a chain and walk arm in arm up the stream until one of them feels the body. They pull the kid out, so very white, and put a blue towel over his face. On the opposite bank somebody shouts: “Here’s the father. Watch out. Here he is!” and an older man, crying, lurches down to the water.

I walk to school most days, except in the winter when it’s really cold and there’s lots of snow. In the warm weather it’s a beautiful walk, with maple trees at the edge of the road and corn fields on one side and all sorts of bugs and little animals in the brush. There are big wire fences that mark off cow pastures down the ridge, above a river lined with trees. We go exploring in these wild areas despite the Do Not Enter signs, with giddy anticipation of being chased by the owner or by a bull, but it never happens. One summer morning, Mike Telfer and Mike McCoy and I go farther than usual along the river until the slowing water spreads wide into reeds and big green grasses. A girl is swimming somewhere and we find her clothes, then we hunt her down and finally corner her in the grass. She’s a bit older than we are and sprawls naked on her stomach, her skin splashed with mud, crying and begging us to go away. We stand over her in triumph, not quite knowing what to do. I’ve never seen a naked girl before.

We talk about girls a lot, but we don’t know anything about sex. Mike McCoy often says he’d like to get Karen Schwartz down by the river, but nobody believes that he knows what he’s talking about. Mike Telfer's girlfriend is Tracy Katz, who has beautiful teeth and olive skin and is taller than all of us. One day when we play kickball she just hikes up her skirt in order to run, not caring that she’s showing us her white panties. We sometimes dance during activity period at school and I dance with Betsy Johnson who lives on a muddy farm, isn’t very pretty and wears braces. We do the box-step, at arm’s length at first but slowly closer until we press into each other and I feel how warm her body is. Mike’s mother takes the four of us to see My Fair Lady in Chicago. Mike puts his arm around Tracy in the theatre but I don’t have the nerve and just put my arm on the back of Betsy’s seat until it falls asleep.

The hesitation to act - fear of offending or just plain fear - is a recurring theme in my life. I don’t kiss a girl until I’m 17, don’t have my hands on a girl’s body until I’m 20. I’m a virgin at 21. Without laying a finger on them, I share a bed at various times over the years with Barbara Dunn, Erica Johnson, Kathy Hawkins, Elaine Cantor - who’s wearing a see-through nightgown, Cindy Schwartz - who's wearing nothing at all, Marilyn Griffin and Karen Cloutier - together, drunk, in a Paris hotel room, Michel Dahlin - who is there for the express purpose of losing her virginity (she didn't), Hildy Green, Doris Pong, Frances King, Jean Thomas and Linda Kilburn.

Chapter 2. Switzerland

In 1959, when I’m about to pass into seventh grade and the Beloit Junior High School, my father is again promoted and we move on. The Warner Electric Brake and Clutch Company is sending him to Switzerland to replace the local manager who is suspected of embezzlement. It’s only seven years since we got here on the boat from Germany and now we’re leaving. When we get to Zurich, my father visits the bank armed with documents, closes the company accounts, then goes to the office and fires the manager.

I was made a US citizen on my 10th birthday, in 1957, after answering some easy questions about US history. Now I want to stay in the US. I’m told that the move is temporary, just a couple of years. In reality we never come back, all of us together. My father dies in Europe 20 years later, a Swiss citizen, having again changed his past. My mother doesn’t return until 5 years after that, to live near Birgit and her family in Virginia. My younger sister Kirsten, born in the US, the only real American among us, four years old when we leave, lives in Europe permanently, her English spoken with an accent as a third language. I next see the US six years later when I come to Boston to go to college. The immigration officer examines my passport, asks a few questions, says, “Welcome home, sir.” I burst into tears.

The trip to Switzerland is made in winter on the ocean liner Cristoforo Columbo, sister ship to the ill-fated Andrea Doria, a backwards voyage of discovery. The first two days at sea and the first two in the Mediterranean I’m horribly seasick. We land in Genoa, travel by car the rest of the way. When we arrive in Zurich we camp in an enormous suite with a giant balcony at the Bauer au Lac, a luxury hotel overlooking Lake Zurich. Mysteriously, I sprout dozens of warts on my back and a local doctor is called in. He burns them off with an electric device as I sit on a stool, the smell filling the room.

We move into a large modern apartment, the top floor of a two-story house in Herrliberg, a semi-rural suburb of Zurich. At night you can see trains moving like tape-worms on the other side of the lake. Since Birgit and I speak German passably well, we’re enrolled in the local public school. I hate it. From the very first day until the end of the school year in June, I hate every minute of it. The kids aren't bad, nobody is intentionally mean to me, no teachers pick on me or yell at me. But I’m treated by everyone, irredeemably, as an unwelcome stranger. I don’t have a place in their world and they don't want me there. I meet the same passive hostility many years later on a ferry in the Virgin Islands, standing because all the seats are taken by the local black kids. Eventually I stand in an empty spot near the front rail, where I get soaked with spray once we hit open water and all the kids laugh because they know not to stand there.

On one of the first days at school, my class has a math drill where we all stand by our desk and only get to sit down, one by one, if we’re first to answer a short calculation problem posed by the teacher. The questions aren’t hard, but I haven't developed tricks to solve them fast, so someone always has the answer ahead of me. I’m the last one standing, a satisfying demonstration to the class and the teacher that foreigners in general and Americans in particular don’t measure up to Swiss standards. From the smartest student in Beloit, I've now become the dummy of the class in Herrliberg.

The school building is Calvinist-austere, the teachers are male, gray and unapproachable. The kids in my class stare at me but few, apart from their leader, a likable athlete named Achie, ever talk to me at all. Achie is a nice, good-looking guy who sometimes walks part-way home with me and is completely dumbfounded by my presence in Herrliberg. The only thing I don’t mind about the school is gym class. This is partly because I’m surprisingly good at dodge-ball, but also because the gym clothes the frugal Swiss parents bought their daughters a few years ago are now a bit tight.

My German is pretty good but I don’t communicate well with the local kids, who speak a Swiss dialect. When I try to speak in dialect they openly laugh at me, so I stop trying. They don’t want me to be one of them. I have to learn to write with a steel quill and ink; penmanship is a standard subject and most of the kids write beautifully with their quills. I can’t. This happens to be the year when students are divided into three groups for separate instruction in the next grades: those who will go on to a low-level vocational education, those who will study for the baccalaureat – the equivalent of a high-school diploma, and those very few who will be prepared to go to university. I’m placed in the middle group. IQ doesn’t matter here in Switzerland, my education will stop when high school is over.

How this is possible is only clear to me many years later, when I realize that Swiss education consists of memorizing approved facts and opinions. Those who memorize best go on to university, to eventually teach the same memorization to those who follow. The development of criticism, creativity and problem solving have no place in a society where everyone wants everything - like writing with a quill - to remain exactly the same.

My rescue from Herrliberg takes place in the fall, when my father moves his office to Lausanne, on the sunny side of Lake Geneva, in the more relaxed French-speaking part of Switzerland. This time I leave no friends behind.

Chapter 3. Grandvaux

My parents enroll Birgit and me as day students in local boarding schools and rent a house high above the lake in the village of Grandvaux, a wine-growing community ten miles from Lausanne. It's a chalet with terraced yards that fall away to the street below. Kirsten, now six, is enrolled in the local public school, which welcomes foreigners in a cunning, provincial sort of way. Many years later, by paying large sums, my father gets the commune to sponsor him for Swiss citizenship, a difficult feat. I live there four years, my parents just a few more - not a long time to be anywhere - but it’s the only place I think of as "home" until twenty-five years later when I have my own family.

Kirsten takes to French as I had taken to English at that age and is quickly fluent, with no accent. It takes longer for Birgit and me and we never manage to get the pronunciation exactly right because some French sounds just don’t exist in English; but some are also used in German, so in a year we can pass for Swiss in France and are certainly never identified as Americans.

Birgit’s school, Le Manoir, a “finishing school" for girls aged 13 to 18, housed in a chateau-like building in the leafy outskirts of Lausanne, is run by a Madame Decorvet who is well aware of all the trouble that girls can get into when away from home.

My school is the Lycee Jaccard, run by the Jaccard family which consists of an older Monsieur Jaccard, Sr. with a bald head and large blue suit; his hectoring wife who is actually in charge; his older brother, an upright, benign Colonel Jaccard in uniform; a small, active Monsieur Jaccard, Jr. with a slim, erotic wife who has the attention of all the boys; and a plain Jaccard daughter, married to a brassy, moustachioed North African named Monsieur Ziaoula.

The school houses 100 boys, aged 9 to 20, on two hundred yards of lake frontage in a suburb called Pully, and includes an ornate residence building with balconies of wrought iron where the boys, Jaccards, teachers and Italian serving staff live and dine, and a severe classroom building of four stories that is also the administrative hub. Here the senior Jaccard sits in an office with buttons on his desk that light up a small red bulb on the outside when he is busy, and a green one when you may knock to see him. When you do knock, he shouts, “Pouvez entrez,” through the thick oak panels. Here he receives the checks that parents write out for him. The school also has a boathouse, a dock, an athletic field with a cinder track, an asphalt basketball court, an unused crumbling gym, and access to tennis courts and a soccer field back up the hill.

The school is founded in 1900 by Marius Jaccard-Depallens, the father of Jaccard, Sr. and a professor of science and photography (then a high-tech field) in Lausanne. Construction of the great buildings is started in 1912, completed in 1914. They have just been occupied when the First World War breaks out and the school is closed. After reopening, and for twenty years between the Wars, the school is at the height of its success. A Swiss education is fashionable with rich British and American families, who want liberal education for their sons, and French. The school is closed in 1939, again revived after the war, now by Jaccard, Sr., but by the time I arrive in 1960 the new demands of American and British universities have already taken a toll. Students now must prepare for the SATs or the O-Level and A-Levels, a challenge that Marius Jaccard-Depallens might have met but that is beyond the understanding or capability of his genteel, bickering descendants.

Teaching is a ramshackle affair. Monsieur Ziaoula and Jaccard, Jr. teach business classes to the older boys, the barren Jaccard daughter teaches accounting, the Colonel teaches physics. The rest of the academic staff comprises a dozen instructors of various nationalities whose teaching skills vary widely and who frequently move on. They are given a bedroom with a lock, meals with the students in a vast dining room that holds three immensely long tables, and one glass of wine on Saturdays. They make up their own curriculum in whatever subject they claim to teach and must perform house duty on assigned evenings.

In this environment of quiet mediocrity, learning falls near the bottom of everyone’s list, students and teachers alike. I am from the start, again, the smartest kid in the school but it doesn’t get me very far. Sports are important, and girls, and I don’t yet have experience with either one.

Despite my lack of status, the years at the Lycee Jaccard are a pleasant blur. I can’t tell one from the next, it's a feeling of permanence even if being a teenager isn’t that much fun. Long, boring summers. Winters in the mountains. Lots of sports - soccer, rowing, ice hockey, skiing, competitions against the other schools in the area. Fooling around with the guys, getting into very minor trouble, seeing the girls now and then.

But the girls are inaccessible to me. I ache for love. I fall in love with Miriam Coleman, but I don’t know why. Probably any girl would do as well because there aren’t any practical consequences, it’s all in my head. I'm a year younger than most of the girls, a big difference at that age, but the real problem is that I have no confidence in myself - and think I'm the only kid who doesn't. Part of the problem, too, is that the girls aren't involved in our life - not in our classes, not hanging around after school, not in the neighborhood. We Lycee guys think of them as alien beings and really know nothing about them. After leaving Betsy Johnson and Tracy Katz in Beloit at age 12, I'm not in daily contact with girls again until graduate school, 15 years later.

Towards the end of my time at the Lycee we have socials with girls schools in the area, although never the Manoir. At one of these I dance close with a girl in a tight black wool dress, inhaling the feel and smell of her. I hope I'll see her again. In the car driving us back that night, the radio announces that President Kennedy has been killed. Most of the kids at the Lycee are not American but the next day classes are canceled and we spend hours around the TV in the school lobby. It's the same days later for the funeral.

Chapter 4. Pierrepont School

After four years of Lycee Jaccard, my parents realize that the academics are lacking. Checking around, they find that the brother of Barbara Dunn goes to a British “public” school south of London. (In England, private schools are “public” schools and public schools are “grammar” schools.) Knowing no better, they enroll me. Recognizing the pitiful instruction at the Lycee, I don't resist.

Once I arrive, the Pierrepont School in Surrey is the worst nightmare of British boarding schools. It lies in the middle of large fields and woods, a dilapidated fake-Tudor estate with cramped passageways, dark paneling and few windows. The nearest village, Frensham, is a 20 minute walk away and consists of a post office and three cottages. You might as well be on the moon. In order to attend, I first must acquire an entire wardrobe of gray clothes from Harrods - gray shirts, gray pants, gray jackets, gray socks, gray and burgundy ties, black shoes, white handkerchiefs and, for a change on Sundays - to be worn to chapel - a black blazer with a large silver crest. The gray shirts have detachable gray collars so you can wear one shirt all week but get a clean collar every three days. The school buildings have no heat. The school has many rules, most of which have no purpose beyond instilling a sense of subordination. Discipline is imposed by a hierarchy of student “prefects” and a "head boy", who are empowered to report infractions of the regulations. The food is homogenized and smells like burnt aluminum.

On the back wall of the headmaster’s study, like a gun-rack, is a collection of canes. For various offenses you can receive from one to six “strokes of the best” on the seat of your pants. The smoking of cigarettes is the most heinous crime. Somewhere in the papers that my parents signed there must have been an authorization for this kind of violence but apparently they didn’t read it. Or maybe caning is so normal that no permission was even asked. I decide from the very first moment that I will never allow myself to be caned, no matter what the consequences. The other students are more relaxed about this, having repeatedly been beaten during their years in the British school system.

You've got to wonder about a country where humiliation and abuse are standard elements of education, and you get promoted to "prefect" or "head boy" so you can get other students in trouble. Why so much punishment? At the Lycee there wasn't any. I'm there only a year but for most of the boys this is how they grow up, not living at home, protected and guided by their parents, but sent away at an early age to be raised by a cold institution; no wonder their emotions are stunted, they're afraid to be criticised, and are quick to make fun of others. Why do the parents think this is good? And for most of them (as in Switzerland) this is all the education they'll get.

The school is divided into three houses, Agincourt, Waterloo and Trafalgar, with seventy students in each, aged 10 to 19. The headmaster, Mr. A.G. Hill, a very decent man, is married to an astonishingly beautiful woman whom the boys call “Wiggles”. For the rest, the women of the school consist of Matron and Cook, whose real names I never learn, and the wives of several teachers, most impressively the hard blonde wife of the chaplain [I'm not making this up] who looks and dresses like every boy's idea of a prostitute.

I'm in Agincourt, and the very first night I'm turned out of bed at midnight by the head boy and prefects, who demand that I hand over my cigarettes. I tell them I don't even smoke (nobody at the Lycee did), and of course they don't find any in their search, but they don't believe me, then or during the rest of the year. I resent this harassing, meant only to show me my place, and instantly dislike the head boy, S.J. Wright. I get revenge in the spring when I displace S.J. Wright on the track team.

The obsession with smoking as the ultimate crime makes no sense. The Headmaster himself and "Wiggles" smoke like chimneys, as do the rest of the staff. The physics master, Mr. Tugwell, has a broad nicotine streak right up the side of his moustache and permanent yellow stains on his fingers. Maybe it's just a way to ensure that everyone gets punished. [And maybe to deflect any idea that real crimes like bullying and sexual abuse even exist.]

The prison-like atmosphere encourages quick bonding. Jimmy Lee from Singapore, Malcolm Scott [Scotty], Geoff Cox, Richard Tiplady from Brazil, Brian Dunn (Barbara's brother) and Adam Miller become my friends. Adam is an American and our leader. He's good-looking in a compact, informal way and supposedly has had sex with a girlfriend in a London suburb. He leads smoking expeditions into the gardens and fields around the school, and in the spring initiates Sunday morning breakfasts, where we sneak off to a hidden spot on a hillside and cook eggs and bacon over an open fire. I go on the smoking expeditions even though I don't smoke. I'm taking a big risk because I'm determined that I'll be kicked out rather than be caned, but I'm part of the group, so I go.

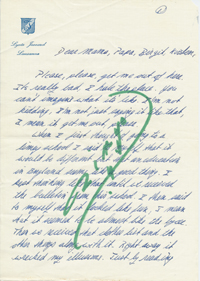

Every day for the first week I'm there, I walk out to the fields in the afternoon, face away from the school, and cry. I beg my parents to get me, promise to study on my own, even chemistry, if only I can go back to the Lycee. They say give it a chance. By Christmas they're making arrangements for me to go to the Ecole Internationale in Geneva, but by then I tell them I'll be ok. Things have loosened up as I get used to the system. I hate the stupid rules, the uniform, the cold, the food, but I'm happy to have friends and I'm learning things in school for the first time in years. Most notable is my math teacher, Major Marstrand, who helped design bombers during the war, an old round man with false teeth, a black gown, and a habit of holding a chaulky hand to his forehead as he talks through problems on the blackboard. I'm the only student who actually pays attention, and in turn he spends much of his time talking to me.

I'm pretty good at sports from my years at the Lycee, soccer, cross-country, track and field, and now rugby, where I'm fast enough to play three-quarter for our house, with only Scotty speedier on wing. Rugby is brutal, we warm up by tackling each other hard, so we're already hurt before play begins even though most matches are just against the other houses. Kids break collar bones, a leg, Geoff Cox loses his front teeth.

On Sundays, after the Anglican service, we have time off and sometimes a few of us go walking in our black blazers. On misty days, the country-side feels hundreds of years old, with no change in the isolated stone houses that loom up, the spreading trees in large fields, the thick dripping hedges at the sides of the road.

A couple of times, girls schools come to Pierrepont for an evening social. These are events where little time can be wasted getting to know each other. Outside, in the darkness of the trees, I kiss a girl for the first time, with wet tongues and lips, Gaye Wyse of Poulters Bricke Cottage, in Crookham, Hants, who sends me a Christmas card later that year.

Because the Dunns keep an eye on me, I go home with Brian once in a while and find that his sister, Barbara, has been transformed from the plain girl I knew in Switzerland. She's been to "charm" school, where she learned to do her hair, wear her clothes, and use make-up. And she's now in secretarial school, learning shorthand and typing. Slowly, over the year, I find I'm in love with her, and I'm pretty sure she is with me, too.

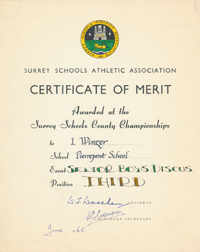

I spend a lot of time at track and field. Despite my modest bulk, maybe 140 pounds, I'm so good at the shot-put and discus that I represent the school at track meets, where I almost always win. My opponents are much bigger, but I've figured out the mechanics. I take third place in discus at the Surrey County meet, where brawny guys from the grammar schools can compete, and am told I should win the All-England public schools championship, where they can't. But it happens that the SATs are held that weekend.

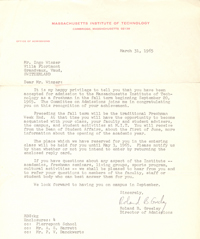

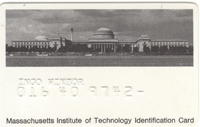

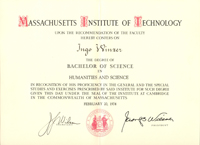

During the spring vacation I'm back home in Switzerland when my mother comes running up the stairs in the morning, waking me up. "Ingo, ein brief von MIT!" Still in bed, I open it and read, "Dear Mr. Winzer, It is my happy privilege to tell you that you have been accepted for admission..." I'm happy I'll be going to college in the US, but don't realize the school is a big deal until I'm back at Pierrepont and Adam casually asks me one day if I've heard anything from MIT. I say yeah, I'm in, and he's stunned, tells me it's the best school in the world.

The headmaster congratulates me, now school is easy, I'm winning at sports, I'm in love, Barbara and her parents come down once in a while, and Brian and I often are up at their home in Twickenham. My sister Birgit also comes over to visit and the four of us have a lot of fun. School is finally over in July. But with just a small break, life now gets serious. In early September I step on a plane and head for Boston.

I leave Barbara behind. Although we've never even kissed, she's my girlfriend and I ask her to hold on to the signet ring my father gave me. That winter, she comes to New York to visit an aunt and I fly down, we spend a great day together, her rabbit coat shedding all over me. I stay overnight, her aunt puts us together in a bedroom, but I don't want sex with her, even if I knew how. We sleep in the same bed and the next day I'm back in Boston.

The practical side of things eventually sorts itself out. I use the excuse of Barbara back home to avoid dating in Boston, but in reality I know there's no future for us. She probably feels this even more, now out in the world, working. At the end of spring she mails me back my ring, with thanks for the good feelings. We never break up. A number of years later she passes through Boston, now with a husband and two children, headed for California where he works. She's immensely grown up but still the same warm, charming girl. I sometimes wonder what would have happened with us - how things would have been different if we hadn't been separated. Or doesn't it matter, do we become who we are anyway? I try to track her down periodically but her married name is Brown, so good luck with that.

Chapter 5. MIT

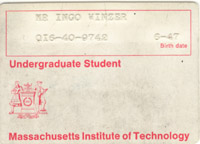

Most students who arrive at MIT are the smartest kids back home, and now they're just average. But most of them at least have a good idea what they're getting into. I arrive with no clue and a complete lack of preparation.

I picked MIT out of a college guide because it was in Boston and I could study architecture. Same for Cornell, Ithaca sounded interesting. If I hadn't been accepted (at Cornell too) I would have returned to Pierrepont for the last year, taken more of the A Level exams and eventually gone to some British university. Until Adam told me so, I didn't know MIT was a difficult school.

When I get to Boston we're herded into Kresge auditorium and shown a profile of our incoming class. I realize I've made a big mistake. The high 600s and low 700s I was so happy about on my SATs put me very near the bottom of the pile. As motivation I suppose, we're told to look at the guy on our left and on our right and informed that one of us won't be around to graduate. Others may have thought with spirit, 'that won't be me!' but I instantly know I'll be that guy.

On my first physics test I get a D, the lowest grade of my life, and I walk in a daze across Massachusetts Avenue, wondering what I will do now. Many years later, when my own children apply to college, I try to steer them to schools that are a good match, not the ones with the biggest names. Why does every parent want their kid to go to Harvard? If they're accepted, they'll probably be miserable because they shouldn't be there.

That's pretty much how I felt that first year, I shouldn't be there.

Why had they let me in? I now think it's because they wanted some diversity (at that time 95 percent of the students were white and male) and I applied from Switzerland with a foreign name. But maybe I'm being unfair to the admissions office, because it turns out that I did belong there, and after I figured out how to study (which took a while) I actually was one of the better students.

MIT was a benign place in those days. Once you got in, they didn't want you to fail. In theory, if you got bad grades you were on academic probation for a semester and if you didn't do better you were 'disqualified'. When my grades go bad, some years later, I'm on probation a record three semesters in a row and they only kick me out after I get three Fs and a D. And then, after I sit out one semester, they let me right back in.

After the first shock, grades weren't really such a problem. That first semester I got a C in the basic physics and math courses, a B in the core civilization class -The Greek Tradition - an A in Form & Design, the first architecture course, and an A in Military Science (I joined ROTC). In those days, at least at MIT, grades meant something. In most courses you expected to get a C, maybe 20 percent of the class got a B, and only a very few students got an A.

My career at MIT is foreshadowed by those first courses. I see I can do well enough in technical fields I don't really understand (like math and physics). I see I'm good at design (and incorrectly think this means I'll be a good architect). And I sign up for ROTC because of the war in Vietnam - I figure I might as well go as an officer.

Vietnam was in our heads every single day during those years - whether we were for it, against it, or just afraid of it. I was for it, at first - we had to win or other countries would fall - but I lost that belief as soon as I paid more attention, or maybe as soon as I became draftable, take your pick. In any case, I quit ROTC after a year, determined to stay away from the war altogether.

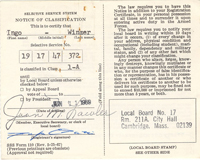

But the war wouldn't stay away from me. College students were deferred from the draft at first, and as my grades slid during the next years that deferment was a bigger and bigger reason to stay in school. I should drop out, regroup, but the draft makes that impossible. Finally, student deferments are abolished, I'm declared 1-A, ready for service, and the draft lottery awards me number 69, which pretty much ensures I'll be called up. All the assholes I know get numbers in the 300s.

It wasn't until August 11,1970 that I actually was ordered to Cambridge City Hall, where buses took us to the Boston Navy Base for a final physical and induction into the army, but I'll tell my draft story now.

First, a philosophical note: I have cervical ribs that cut the circulation to my arms if I do pullups, hold a rifle over my head or fire one lying down; I wouldn't last a week in the army - but I don't discover this until much later. So, I spend years worrying about nothing. (And it never occurs to me that in any case, the army won't send a guy from MIT who speaks perfect French to patrol the paddy fields. He'd be aide to some colonel or general.)

By 1970 it's pretty clear that we're still in the war only because nobody knows how to get us out. I have no quarrel with the Vietnamese, don't feel any patriotic duty to kill them. And I'm not getting my ass shot off to save Richard Nixon's presidential reputation. So, I plan to fail the physical.

Some guys avoided the draft by puncturing their eardrums or mangling their fingers. My best friend Lance ate himself over the weight limit, Al Myerer showed up for his physical painted half red, half blue, my friend Clyde found he had high blood pressure to begin with. I decide to fake high blood pressure, stay up all night, drink loads of caffeine, pop salt pills to retain fluid, practice tightening my muscles. Testing at home, I'm way over but at the real physical they clock me at exactly the limit, 140. It's one of the early tests so I have time to do something else, but I don't know what. The hearing test is too easy to fail, everyone tries that, and if I have a fit and fall, maybe hit my head, it's just a temporary measure. By the time I'm sitting with a group, waiting at the last station, a quick interview with a doctor, there's nothing else to be done, so I put my face in my hands and start crying - tough to do in your underwear with 500 other guys in the room, but once you start it's easy to keep going. Eventually one of the doctors notices me, talks to me, sends me home.

In the early years they would have taken me anyway, but now they just call up the next guy. I'm elated to beat the system with its own rules - after all, I could have refused to step forward at the induction ceremony 30 minutes later and gone to jail instead. I didn't agree to the whole draft business, so I don't mind thwarting it. I go home and the 500 other guys don't.

They later have me back for psych interviews but it's easy to be withdrawn, distracted, unresponsive. I learned how by seeing people with real mental problems at my weekend job, orderly in the emergency room at the Beth Israel Hospital.

Chris Davis, later a famous trauma doctor in Seattle, took me along to Boston City Hospital one night in my sophomore year, where he volunteered in the emergency room, registering patients. I had never seen anything like it.

I apply for a job at Beth Israel, walking distance from school, no experience, no skills, but they don't care, they need me, lots of turnover among orderlies. I start afternoon shifts, stocking the treatment rooms, putting clean sheets on stretchers, wheeling patients up to x-ray, carrying blood samples to the lab, cleaning bedpans, sterilizing equipment in the steam autoclave, getting supplies from the kitchen, making coffee in the big percolator.

Doctors rotated through the emergency room six weeks at a time. The place was really run by the head nurse, Sally Price, a short, formidable woman in her fifties who took crap from nobody - doctors included - and was very protective of her nurses, most in their early twenties. Every once in a while a resident would pick a fight with her but the senior doctors were in her pocket and he'd have to back down.

I'm writing at length about being an orderly because this was the best thing I did in Boston, school included. During four years, on and off, part-time, full-time, I meet thousands of people who need help, their defenses down. If you want to learn what people are really like, this is it. I work double, even triple shifts. I'm good at it, and I become part of a very tight group of young nurses who treat me as an equal. Growing up separate from girls since the sixth grade, I'm now right in the middle of them, working beside them, hanging out with them, going drinking with them, to the beach, to their weddings.

I move to the midnight shift and, because there's a shortage of nurses and I'm highly competent, it's soon just me - doing things an orderly isn't supposed to - and a single nurse, dealing with maybe a dozen cases a night, some very serious with cops and doctors and blood, but sometimes nothing for hours, just us two shooting the shit while the doctors sleep. The first year it's Kathy Hawkins, 26, who later joins the war as a flight nurse. I have a crush on her, and I call it a crush on purpose because that's all that was possible. We spend a lot of time together, at work, not at work, hanging around, talking, drinking, a close hug now and again.

And that's how it goes later with Eleanor, Karen, Elaine, Marilyn, others. Lots of hours together, just the two of us. I learn far more about women than most guys ever do, probably why my closest friends in life have always been girls.

Among other things, I learn that a woman will let you know if she wants a relationship - which my nurses, in my case, don't. But I do desire these women and I'm a safe little flirtation for them too. Elaine and Cindy in skimpy nighties when they call me over late at night, more than once, on a silly pretext. Staying over at Kathy's, Karen's, Pat's, Eleanor's, Elaine's, Cindy's, not necessarily on the couch. A kiss once in a while at some group party. And at the end I actually do sleep with Marilyn.

The nurses keep being young and in short supply because they marry out. Not to doctors but to guys from their home towns. One or two (Cindy) have short affaires with doctors but most are Catholics with pretty straight morals, although we kid around about sex all the time.

My job couldn't be better, but at this point in my academic career - or maybe just at this point in growing up - I'm otherwise having a hard time.

One reason is that I'm restless, unable to concentrate, it's physiological I guess - later in life I calm down. I can't sit still and study. I think I might be missing something. At the slightest pretext I join a friend to go downtown, get a sandwich at Ken's. You can always count on me for a few hours playing bridge. Other guys take breaks from studying but I'm all break. I go for long walks at night, hours, nowhere in particular, best in the rain or snow, tramping relentlessly.

The second reason is deeper, but maybe also more common when you're young. I realize that nobody is running things. No parent or committee is tracking my progress, there's no master plan for me, there's no guarantee things will work out. If I do something stupid, maybe no one can fix it; if I do something good, maybe no one will notice. Sure, friends and parents and teachers will help, but when it comes down to it, everything is now up to me. It's a bleak prospect. I don't yet like this freedom, don't feeling very competent in that department. It's easier when someone else is in charge.

Chapter 6. Sigma Chi Fraternity

The nurses, the draft, trouble with school, problems with women (see below) - in the background of all these developments was the Sigma Chi fraternity, which I joined warily as a freshman and where I met guys who later became my life-long friends.

Fraternities provided housing for about a third of the undergraduates at MIT at this time and weren't much supervised by the school, mainly because we weren't much trouble. There was a fair amount of drinking but it was legal, the age in Massachusetts then was 18. And even though we might get drunk once in a while, it wasn't on purpose - there was no binge drinking, no beer pong, no hazing, no drunk driving, no date rape. Maybe it was tame compared to what might happen at other schools, but then, we were the smart guys.

I came to Rush Week before the start of school. I thought I should join a fraternity, even though I had no idea what that really meant. Once there, and after visiting a half dozen, I wasn't so sure it was a good idea. I got offers from Sigma Chi, Sigma Nu and Theta Chi - the local animal house - but while most guys make up their mind after a day or so, it took me a couple of months. I lived in one of the dorms during that period, East Campus, a depressing experience that taught me a lot about the life of real nerds. OK, we were all nerds but the fraternity guys at least had some social stuff going on.

I didn't want to be a brother to 40 other guys - who can possibly be that sincere? - and I found the fraternity stuff silly. Flags, symbols, traditions, prayers, dressing for dinner, I knew all that from Pierrepont. On the other hand, being a fraternity guy was a challenge, part of growing up. And I could all too easily see myself doing the opposite, nerding it in the dorms, studying because there was nothing else to do, not learning how to be social. So I joined.

Years later, many guys said the fraternity got them through MIT. I can't say that because it didn't - I got kicked out anyway - but also because I never really bought in to the whole idea, and I moved out of the fraternity house at 532 Beacon Street as soon as I could, the start of sophomore year. Still, the place provided a home of sorts and I spent a lot of time there.

A word at this time about my parents. When you're a kid you don't really notice your parents until you're eight or so - and if they're not mean to you, not even then. My parents were nice. They weren't strict, they didn't lecture or shout or criticize, they never made me feel bad. I imagine I must have been slapped once or twice, but I don't remember it, or a single time they did or said anything nasty to me or my sisters. To me this was normal, so it was a surprise to find out later that many parents aren't like that.

On the other hand, by my teens I was very aware that my parents didn't get along, and that that wasn't normal. In Switzerland my bedroom was next to theirs and I would hear my mother complain in muffled, vehement tirades. It didn't bother me a whole lot, I had other things to worry about, but the lack of intimacy and openness between my parents meant that I never dreamed of confiding to them any problems of my own.

My parents had had to marry - pregnancy - maybe were never in love, my father first dated my mother's sister. It was the war, a desperate time. After the war my father and mother came to America, where she never seemed to belong. If it's tough for kids to constantly move, it's got to be worse for their mother. I don't remember that she ever had a close friend. At some point later, in Switzerland, my father wanted to divorce, she wouldn't let him. They were still married twenty years later when he died, but had lived apart for years.

So the fraternity wasn't a substitute home for me, as it was for many of the guys, because by that time I didn't feel I had much of a home anyway. And maybe for that reason I never became a strong fraternity supporter later on. I went to reunions and eventually even hosted a few because the other assholes in my class were inept in that department, but just as a practical matter - not from nostalgic fraternity feeling.

It was through the fraternity, though, (and for the record) that I had my first apartment, at 434 Marlboro Street in the Back Bay, second floor, living for a year with Surfer Jim Vanderlan (who had just been kicked out of MIT - a fine example). And then I lived with a bunch of the boys at 22 Magazine Street in Cambridge, with Lance Hansche at 395 Broadway, with Lance and Clyde Rettig at 46 Dana Street, and then with Lance and Clyde an hour north at 802 Summer Street in Manchester-by-the-Sea. In graduate school at Boston University I lived on Commonwealth Avenue in Brighton with Dave Kiser as my neighbor.

And (again for the record) it was through the fraternity that I met Erica Johnson, Sue Hodge, Jean Thomas, Candy Kovacik, Joan Nemeth, Nancy Black, Helen Sandals, Linda Kilburn, Lisa Wells, Mary Waddington, etc. mainly from Wellesley College where the fraternity for some reason had a long-standing connection. Most of these women dated my fraternity brothers, which meant I could become pretty close friends with them without any problems.

It sounds like a smart-ass thing to say now, looking back, but from the nurses I got one perspective on life, a very ordered one where they worked and then married back to their home towns to have children, and eventually worked again; and from the Wellesley girls a quite different one, more confused - much closer to my own - because they didn't see a clear path for themselves. Even marriage, which most of them wanted, was just one part of an ill-defined future.

Chapter 7. Work and Women

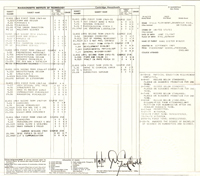

My own future was pretty ill-defined too. After three years of failing to learn much about architecture, then being kicked out and re-admitted, I still didn't know what I wanted to do. My major now was Humanities and Science. I read a lot of European history, a lot of Nietzsche, Italian philosophers, I learned microbiology, neuroanatomy, neurophysiology. I took a course in neuroanatomy lab techniques and afterwards the professor, Jerry Schneider, knowing I was looking, offered me a job as a lab assistant.

So, at 23, I became a full-time worker - my orderly days now over - and a part-time student. My father had coughed up enough for school - although it was amazingly cheap by today's standards - and I paid my own way from then on. Being an MIT employee was a good deal, healthcare was free, tuition was half-price.

Jerry Schneider was an assistant professor in what was officially the MIT psychology department but was actually a small but already famous "neurosciences" center under Hans-Lukas Teuber, the head of the department, and J.H. Nauta, a leading anatomist. Schneider's work focused on how nerve connections are made in the brain and he did this by pressing a hot nail to the head of new-born hamsters, damaging the ear, the eye, or certain parts of the brain, and seeing later in the adult how this early damage redirected nerve fibers to other areas.

The latter part of the process required killing the hamster, turning its brain into microscope slides, and having a good look. That was my job. I killed hamsters in an elaborate procedure that flushed out their blood while they were still alive, pickled their brains in formaldehyde, sliced these into ultra-thin sections that I treated with exotic chemicals to highlight nerve cells and connections, and mounted them on glass slides. I did this for over two years, very happy to have a job but eventually getting bored.

The fun part of the job was getting involved with Dorys Pong, who worked for one of the other researchers. She was petite, pert, cosmopolitain, ten years older, in her 30s, with a six-year old daughter at home and a separated husband off in Asia somewhere. We never slept together but pretty much everything else, sometimes making out in the darkroom at work, the red light on outside. After a year she moved away - ironically to Switzerland - but during that year I lived more at her place than mine, very domestic.

I haven't said much about girlfriends so far because that's really a different type of story, women and relationships can't be explained in a paragraph or two. But with Dorys Pong now in my life for a year, and with four years of Mary Corrigan coming up, I'll give a quick overview.

At the Lycee in Switzerland I thought I was in love with Miriam Coleman. Nothing came of that. At Pierrepont School I was in love with Barbara Dunn. Nothing could come of that. My first year at MIT I didn't even try to date. At the start of my second year I fell in love with Erica Johnson, two years older and dating one of my fraternity brothers. Of course nothing could come of that. Later that year I became involved with Sue Hodge, after she and another of my fraternity brothers split up. This time I wasn't in love, I just liked her a lot and we dated for some months. I knew nothing about sex and our first attempt didn't go so well. So not well, in fact, that I developed tremendous anxiety about it and we never did manage to, a crushing failure. We didn't date very long after that and I couldn't even look at a woman for over a year.

At that point Erica had split up with her boyfriend, we were already close friends, she knew all about the Sue fiasco and it was easy for us to sleep together. But we weren't well suited for a relationship. She was emotional and romantic - everything I had dreamed of in a woman - but to my surprise I found out that I don't actually do well with such intensity. After some months we went back to being friends, which we've been for 50 years.

I had a short relationship with Marilyn Griffin, one of my nurses, near the end of the orderly days. We'd work the night shift, then sometimes have a couple of Harvey Wallbangers at the Windsor Bar on Brookline Ave, 7:30 in the morning, head to her place and screw, no romance at all. And there were girls I sort of dated but not really or not for long, Hildy Green, Jan Whitman, Peggy Olaski.

In the intervals of these doings over the years was Jean Thomas. She dated yet another fraternity brother - there's an endless supply - Stan Limpert. Then she didn't. Then she and I had a few dates, but not sex. Then she dated Al Davis. Then she was back with Stan. Then she got involved with a married man. I thought I was in love with her, but was that love? Or only a fantasy about a fun, smart and attractive girl? And then, how can you love someone who obviously doesn't love you back? Oh, she liked me well enough, we were good friends, but at any moment she could have said, gosh I'd rather be with Ingo, he's so great. She didn't.

That probably wouldn't have worked anyway. Jean, like some other women I've know - Joannie, Jodie, Erica - went from guy to guy, never getting what she hoped to find, and I'm not sure she even knew what that was. Hoping to be hopelessly in love? A fantasy that only works while it's impossible? In a way she was a lot like me but with worse outcomes. She had a child with the married guy, was herself married and divorced three times, became an alcoholic, had difficulties with her teen son, had health problems. I lost sight of her 30 years ago. Women can be as stupid as men, seeking some dream guy who doesn't exist.

The main point about these side trips is that while I had some interesting relationships with women, I never dated anyone more than a few months until I met Dorys Pong - and I'm not sure she qualifies as a true girlfriend anyway, because actually sleeping together was off the table.

After Dorys I don't date for a while. Clyde, Lance and I move out to Manchester-by-the-Sea, an hour north, and we drive in to work each day, it's 1971.That fall I get briefly involved with Leigh Rooney, that spring with Linda Kilburn - another fraternity connection. And later, at Linda's house, I meet Mary Corrigan from Kansas, who's a few years younger and works in a hospital lab downtown.

She's cute but not the most attractive girl I ever date. I'm smarter about women now, though, and she's very nice. We end up together for four years, on and off, but it's strictly weekend dating. We go out with friends, sometimes it's just us, we party, we have sex, we may spend an entire weekend together, but during the week we have no contact. We never live together, never travel anywhere, we're never in love - although I'm pretty sure she'd like to be.

It's the first time I've had a steady relationship, and it's far better than my former desire for all-consuming romance. I realize after a while, though, that from Mary's perspective the situation is not so great, not really what she wants, and I'm sorry about that. But I'm honest with her, she knows I'm not in love, and I work hard to be a good boyfriend. I treat her extremely well, and I figure that if she ever gets tired of this we can easily stop - no harm, no foul. (That's pretty much what happens in the end - but see her letter.)

So much for the review. Later in life I try to find out what happened with Mary and the various women I've known, from Betsy Johnson and Tracy Katz on down, but without success. Aside from Erica and Linda, with whom I'm still friends, they've disappeared. Sure, many women change their name when they get married, but in the days of Google and Facebook you'd think some at least would be visible after a fairly simple search. Not many women were at the Manoir in Lausanne, after all.

Whether I'd contact any of them is a different story. Some would not remember me at all, or only as a bit player in their life. Others might not have favorable memories of me, so what would we talk about? Mainly though, the big fat fact is that none of them have ever tried to contact me. I'm easy to find - type my name into Google or Facebook and I'm right there - so I guess none of them were very keen to be in touch.

Chapter 8. Boston University, Olin

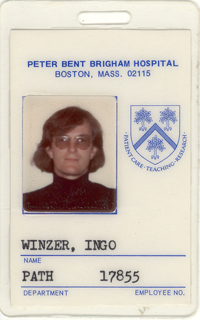

In the fall of 1973 I'm 26, I quit my job, go back to school full-time and get my degree. It's not worth much on the open market, however, since I have no skills, so I get a job in the neuropathology department at the Peter Bent Brigham hospital, making micoscope slides from human brains - not so different from the hamsters but I don't have to kill anyone.

At this time I've moved back into town, to Brighton, where I live at 1431 Commonwealth Avenue. With my degree from MIT and with A's in important subjects like microbiology, biochemistry, and organic chemistry - Harvard summer school - I apply to medical school even though I graduated from MIT with the lowest possible grade average - more A's than anything, but unfortunately the next largest category is F's. I'm not naive but for years I've nurtured the secret hope that the admissions committees will see beyond the surface and recognize that I would be a terrific doctor. Nope.

I receive rejections from the six schools I apply to, not a surprise but a further reminder that the world doesn't run according to what would be best. I don't even tell my friends about the applications, much less the results, because I knew this would happen, but now that the secret fantasy is dead at last - probably a relief - I have to decide what else to do.

Something professional or academic. I've already taken GREs, now will add law boards, business boards, go from there.

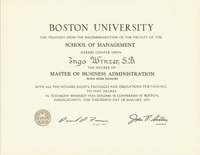

The law boards involve an enormous amount of exact memorization, which I'm not very good at, but I kill the business boards, score in the top 1 percent. I apply to Berkeley, UCLA, Boston University, Northeastern and Harvard. All accept me but Harvard, a surprise to Clyde and David who both went there, so I think I scored higher than they did. I'm tempted to leave Boston and go to Berkeley. California - a new place, new beginning. But BU offers me a chunk of financial aid without even asking, so BU it is. My father generously foots the tuition and more.

Graduate school for me is almost the opposite of my years at MIT. BU is in the second tier of business schools, I'm the smartest kid again. I have my own place, a car, I know how to study, I have experience with women. I'm 28. The courses aren't easy, I don't get all A's, but I graduate early and with high honors. I kill the mathy courses even though math isn't my strength - advanced accounting, operations management, finance. I'm so good at statistics that I'm hired as a teaching assistant, running Saturday morning review classes.

I'm also a popular guy, outgoing, I make friends easily. I make a special point of being nice to the students who aren't very popular - unsure of themselves, socially difficult - it doesn't take much to make someone feel good. I quickly hook up with Juanita Costa, a nice-looking girl from Minnesota and we date until I graduate.

This is a problem for Mary Corrigan although I've always told her to assume that I also date other girls. She's supposedly fine with that, but now it's a sign that things will never work out with me and a year later she moves back to Kansas. I date a couple of other women, Juanita is not a steady item. One weekend I sleep with three different women and am so disgusted with myself that I stop dating altogether.

I make friends with Amy Auerbach and Webb Carnes in finance class, the three of us hang out, go drinking, each otherwise attached so there's never any problem, and we stay close for years.

I'm confronted with the dark side of business when I take a course in advanced marketing. The teacher tells us we'll test if political views can be changed by ads. We'll sign up members of the public, get their views on current issues, then send them bogus political materials in the mail and later see if their views have changed. It sounds benign enough, but once the project actually starts I'm having doubts. We all must pick 20 names from the phone book and cold-call people, tell them we're starting a new poll at Boston University, "like the Gallup poll", and ask them to join. It's stressful for me to call strangers on the phone (see above), but what really troubles me is that we're asking people to do something public-spirited, tell them their opinions are important - when actually we're lying, trying to manipulate them for our own purpose. I sign up my 20 people, but by then I believe the project is morally wrong and I drop the course.

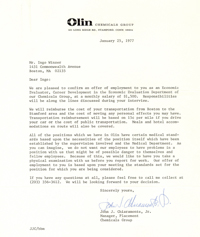

I haven't much else to say about the two years at BU. Everything's fine, everything goes well, no other important stuff is going on in my life, I'm focused on school. I continue right through the summer semester, graduate the following winter. I'm offered a job with Olin Corporation at their headquarters in Stamford, Connecticut. It's mainly a chemicals company, but with divisions that make paper, brass, ammunition, Winchester firearms and Olin skis. My plan is to get experience with a big company, eventually start a small one with some friends, I'll be the finance guy.

A few years later my friends Lance and Clyde actually do start a small company - but without me. They want a finance guy who has experience raising money, which I don't. To my mind, experience isn't as important as who I am, and I don't feel sorry a year later when their company goes bust.

As a lab technician I was making $11,000 a year. With my MBA, I start at Olin as an analyst making $18,000. Over the next four years I'm promoted to senior analyst, manager, then director, making $60,000. (Multiply by a bit more than three to get 2017 dollars.)

I learn at Olin that in large corporations you fill a position, rather than work at a task. I analyze a lot of stuff, provide support for Board of Directors decisions, am well thought of. The president even sends me on a secret mission to scout a possible big deal. But there's not a single thing I do during my five years there that makes any real difference to the company.

I learn that the senior managers spend most of their time undermining each other and that my next promotion - to vice president - will require having a wife, kissing ass, and aligning with one faction or another. I'm much too young anyway, the vice presidents are all in their fifties.

When I'm the corporation's cash manager, working for the treasurer, I sign the expense checks for the top executives - country club memberships, fancy hotel bills, big vacation trips, cars. And I sign retainer checks for law firms, brokerage houses, consultants, others - usually just one line on the bill, "Quarterly Services" or something like that, and a big number. These aren't for real work, they're the cost of relationships. My nominal boss, the assistant treasurer, spends every other day being taken to golf or lunch (yes, three martinis, sleeps it off on his sofa) by someone from the big banks we deal with or the dozens of others that serve our local manufacturing plants.